In trying to understand how preservationist, tenants-rights, and pro-development political factions fit together, I keep coming back to the core facts of the SF housing market, as the different factions have very different interpretations or explanations for these facts, and different views of what that means for potential policies to address SF’s housing crisis.

This post is part of a multi-part series written to summarize insights from moderating the Manny’s Housing Week. Check out the other posts:

- Part 1: History and overview of the main political factions and their core values

- Part 2 (this post)

- Part 3: Exploring SF’s housing market vacancies

Different Outlooks: Demand

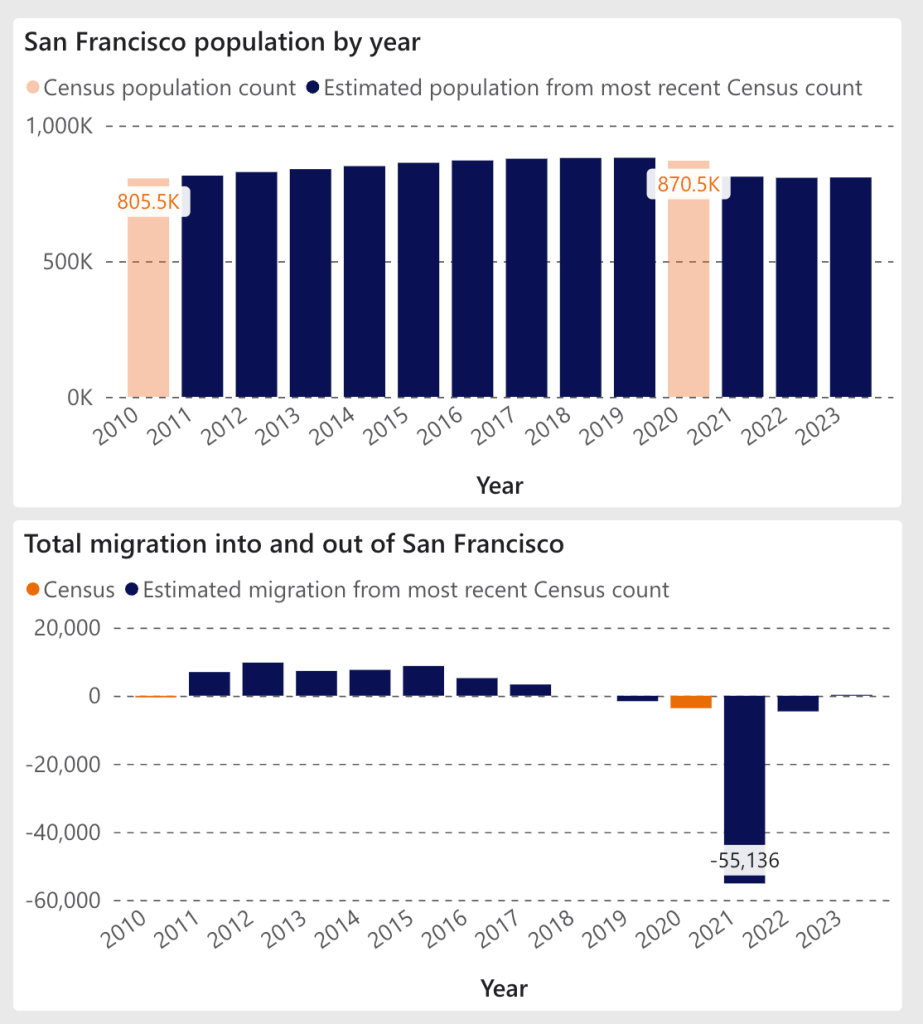

Fact: California’s population is falling, and San Francisco lost about 60,000 residents since 2020 (8% of its population).

For YIMBYs like Ezra Klein, this is attributable to the high cost of living, primarily the cost of housing, and to the cheaper cost of living in places like Texas and Florida (two popular destinations for decamping Californians). I’ve been in meetings where this decline in population is viewed as proof that we need to build more housing to drive down prices to induce demand and get people to move back.

For the preservationists, this population loss should be credited against the state’s RHNA mandates, which were set based on data up through 2019: If those residents no longer live here, we no longer should be required to build housing for them.

In a funny way, both the YIMBYs and NIMBYs could be right: Perhaps people left because of high prices due to slow development, and they won’t be coming back: in this case, the preservationist strategy of slow-rolling new housing actually worked, and the NIMBYs won.

Different outlooks: Current inventory

There are two government numbers which get tossed around a lot when talking about how much “additional” capacity we need to plan for:

- The “Pipeline” of entitled projects which have permission to build housing but which have not been completed stands at 72,000 units as of Q3 2023

- The number of vacant units, which is estimated annually by the Census’ American Community Survey and stands at about 46,000 as of 2023 (margin of error: 5,000 units).

The pipeline

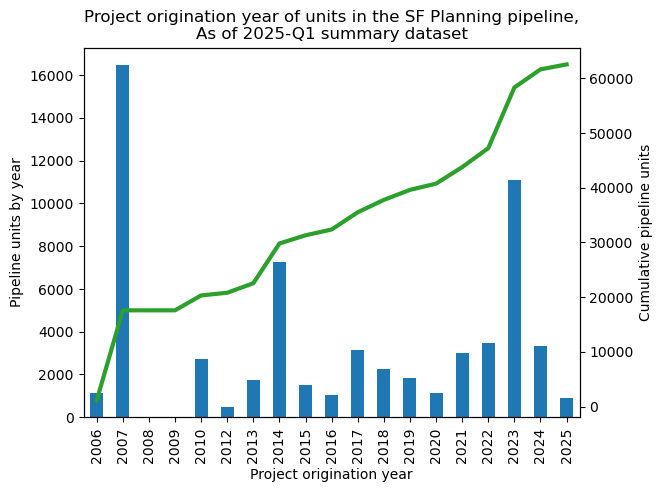

An optimistic outlook would claim that the state’s RHNA goals could be met if the 72,000 units in the pipeline were to materialize, and so preservationists and tenants’ advocates object to encouraging additional development. YIMBYs point to the fact that these putative units haven’t materialized as a reason to discount them heavily, trusting only units which have high certainty of materializing. The truth might be more nuanced.

The pipeline considers all projects which have gotten entitlement from the city to be built, but does not consider the economic feasibility of getting the unit financed, permitted, and built. Many of these projects have been in the pipeline for a long time: looking at the pipeline status as of Q1 2025, about half of the projects have been in the pipeline for over 10 years, and 16,000 units are from projects on Candlestick Point and Treasure Island which were proposed in 2007 and are still stuck in the early stages of development (because these old projects have been in the pipeline since before the global financial crisis, their economics have changed dramatically, delays have compounded as the developers deal with toxic waste cleanup, and the plans have been repeatedly revised as the developer’s financing has changed).

Currently, interest rates and material costs are high, and many of the pipeline projects are uneconomical to build. If financing and material costs drop or the outlook for rent and sales improves, these units could become economical, and market forces could unstick the pipeline.

Despite these challenges, units still get built: San Francisco has produced an average of 4k units/year, and the challenge for SF Planning and the Mayor is to identify how to “unstick” the units in the pipeline (currently under investigation by Bilal Mahmood). One option is to continue to expand zoning permissions, allowing projects to build higher or denser to add more units, increasing the odds that they will “pencil”- this has been the focus of both state legislation like the State Density Bonus and SB423, and the current rezoning effort, which will affect many large proposed projects on Market, Van Ness, and Geary. These changes will definitely grow the pipeline as projects get designed for the higher-density regulations, but may not increase yield if interest rates and construction costs remain high.

While the SF government can control zoning and design standards, they cannot control the market and the government does not directly build housing. Even if we dramatically grow the pipeline we may see almost no housing produced during this period of high interest rates and high construction costs- and then we may see a dramatic influx of new housing if the market turns and interest rates and costs come down.

Vacancies

The discussion around vacancies during SF Housing Week was interesting and nuanced enough that I wrote a separate blog post about it – in short, we have a tight rental market but a higher-than-usual number of units kept off-market by their owners. Owners likely keep these units off market because they are informally merging units, disincentivized to rent or sell them because of rent control and Prop 13, or are speculating on SF real estate- all of which the 2022 Prop M sought to address by introducing a vacancy tax. However, no city is free of off-market vacancies, and if vacancy rate were to fall to a level typical of other cities, we would only see about 12,000 additional units added to the market: far short of the city’s needs.

Different outlooks: Production

Are we “building enough”?

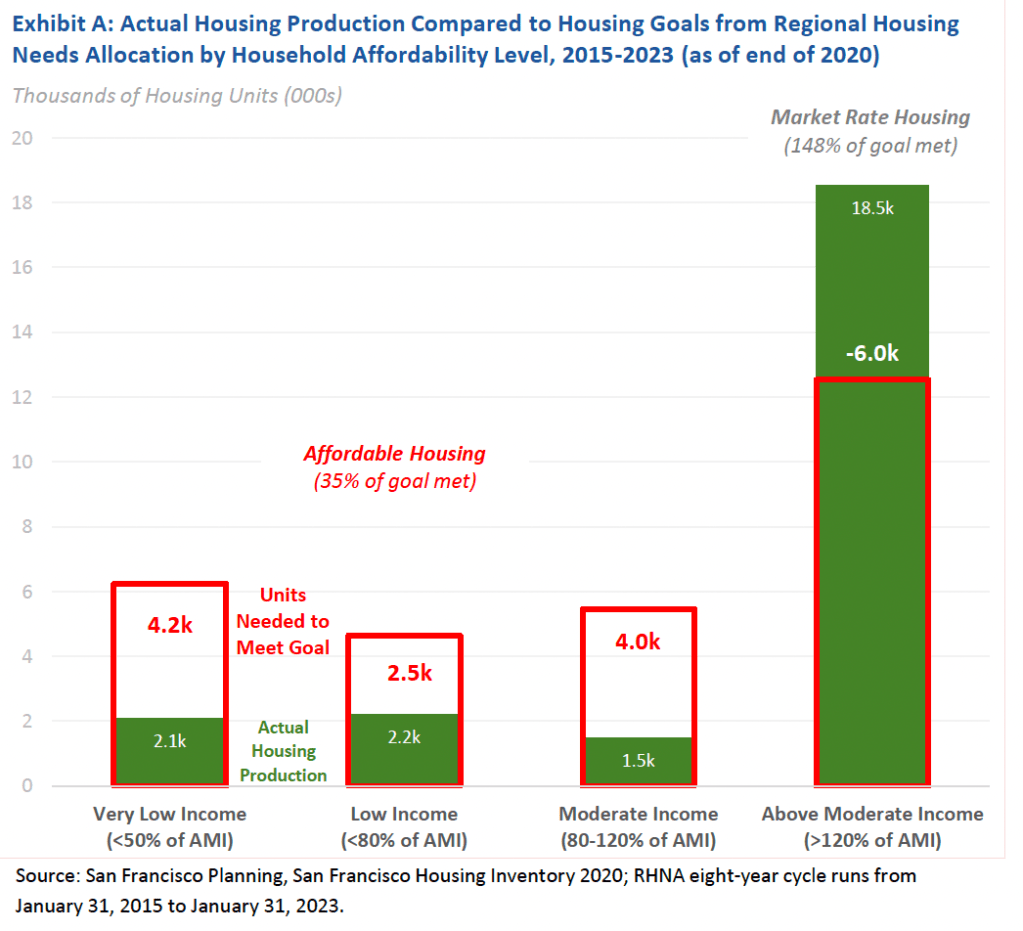

Looking at the above chart summarizing SF’s 2015-2020 housing production from a 2022 legislative analysis would suggest that SF has the ability to exceed its requirements for producing market-rate housing, but it has struggled to produce affordable housing.

This has led to a consistent rift between pro-development and pro-tenants groups: many progressive voices want to see us focus on building affordable housing, rather than “housing at all price levels” – which they view as most likely to produce luxury units in a continuation of the 2015-2020 construction trends. They fear that lifting the overall target of production will encourage more construction of luxury housing, without providing any relief to middle-income renters

A variety of views exist within the YIMBY movement, but the most common view seems to be that this is fine: relieving pressure on high-end housing should result in less competition for the rest of the housing supply, relieving pressure across the board. This is critiqued as a form of “trickle-down economics”, and may place too much faith in efficient sorting, which might not be likely if people don’t move frequently.

A recent report ties the production of luxury real estate to the high cost of permitting and construction in the city: while developers generally prefer to build mid-market units because they are less risky, when per-unit costs are high the only units which can economically be built are luxury properties

A nuance here is that fees from market-rate development are one of the main funding streams for affordable housing: so if we turn off the production of market-rate housing, we will also turn off a portion of the funds for affordable housing.

Different outlooks: Prices

Many times over the week, tenants’ rights advocates would highlight stories of landlords increasing the price when they list a rent-controlled unit, in response to the median rent in the neighborhood being brought up by a new luxury apartment building opening down the street. This

When these stories were shared, I could see YIMBYs visibly fuming (or sending furious slack messages) for such heresy. The truth, as academic studies like Pennington 2021, Chapple 2022 highlight, is nuanced: increasing supply reduces median prices, but to a limited effect.

Because of rent control, SF rents are chunky: take my old apartment in Alamo Square as an example, which saw its rent jump 50% when I moved out in 2013 after only 3 years under rent control. Because a unit’s rent can only be adjusted when the unit is vacant, we only get to observe the price infrequently – even though a lot might be changing in the city. This was the second tech boom, people were moving to SF, demand was surging, and developers were breaking ground on new luxury units in SoMa and Hayes Valley because rents were high. If we’d waited another two years and our unit had gone on the market at the same time as those luxury properties had gone on the market, it might have appeared that the rent on our unit was doubling because of the new luxury units- but in reality, both properties saw high rents because of high demand.

Because market forces aren’t easy to visualize and we only observe rents infrequently, it can be hard to identify causation, which is why academic studies are important. There isn’t a clean world where we can take away the externally driven demand and see the impact of construction on its own, but based on the research cited above and elsewhere, increasing production would produce a decrease in rents, absent any change in demand.

However, the decrease in rents can themselves induce demand: people who moved from SF to the East Bay might want to move back if prices are lower, or more businesses might move to SF, creating a limit for the impact of increasing supply.

As a result, most estimates I’ve seen suggest that dramatic increases in housing production would only reduce rent by 5-15% in SF, which would hardly be enough to address the current housing crisis (Austin, which went through a particularly impressive building boom, saw rents drop closer to 23% from its pandemic highs, but may not have as much pent-up or induced demand).

I’d also note that the induced demand can sometimes actually make the problem worse if a speculative bubble emerges: over the last two decades Vancouver saw a major boom in construction of luxury condos, targeting overseas buyers seeking a safe and diversified investment. Vancouver became such a desirable place to invest that overseas buyers soon were competing for properties at all income levels, outcompeting locals and causing an affordability crisis for locals. A vacancy tax introduced in 2017 helped curb this, but was not a complete solution and could not help the families who had already been displaced.

Conclusions

Even when we’re looking at the same facts, we can have wildly different interpretations- and because the housing market as a whole is slow-moving and each city’s policy, business, and housing landscape is unique, the lessons from other cities can’t entirely guide us. The goal of this post was to lay out some of the core facts which are often raised in housing debates, with the hope of creating better discourse with more respect for the nuance from each side.

Leave a comment