I spent my evenings last week on-stage at Manny’s Community Event Space moderating talks about SF housing for the first “Understanding SF Housing” week at Manny’s. We had a packed schedule:

- Night 1: The Future of Housing in SF: Debate with Laura Foote (Yimby Action) and Maria Zamudio (Housing Rights Committee)

- Night 2: How did we get here? The History of (Local) Housing Policy with Conor Dougherty (NY Times; author of Golden Gates) and Heather Knight (NY Times)

- Night 3: Affordable Housing 101: What is it? How is it built? With Sam Moss (Mission Housing) and Dan Adams (Mayor’s Office)

- Night 4: The Future of SF Housing: Our New Zoning Map with Planning Director Rich Hillis

- Night 5: The rent is too darn high! Managing gentrification and preventing displacement with Fred Sherburn-Zimmer, Housing Rights Committee, Marsha Powell (formerly SF rent Board), and Shanti Singh, Tenants Together

Moderating such an incredible set of speakers gave me a lot of respect for the depth of experience and knowledge of the activists in this space, and how difficult the political path for improving the San Francisco housing crisis can be.

This series of posts captures some of my high-level notes about the insights that I had from the conversations with our speakers on and off the stage, with our audience members, and in other similar meetings over the past few years.

Check out all the posts in this series:

- Part 1: this post

- Part 2: Same Facts, Different Outlooks

- Part 3: Exploring SF’s spooky housing market vacancies

How we got here

Much of San Francisco was built before 1920 in waves of suburban growth out from the city center, facilitated by streetcar lines and (much later) the automobile. In the immediate post-war years a combination of redlining, the GI bill, and the loss of military jobs in the naval shipyards led to more development of the Bay Area’s suburbs and less infill development.

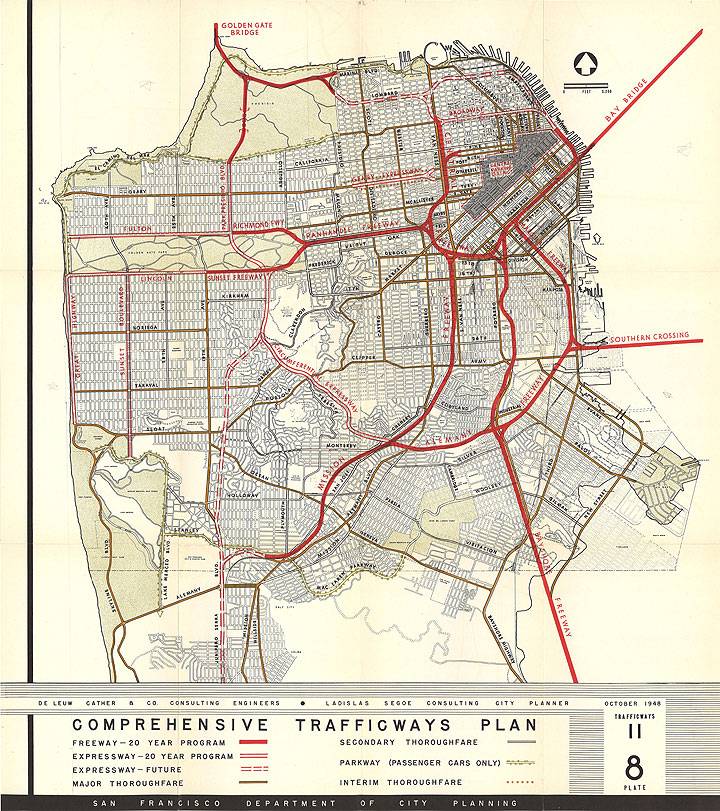

In the 1940s through 1960s, new urbanism and the “city beautiful” movement imagined a San Francisco of highrise residential complexes connected to the rest of the bay by high-speed highways. The “Urban Renewal” of the Western Addition starting in 1953 bulldozed the African-American heart of the city, while the Embarcadero Freeway cut off downtown from the Bay – and more highways were coming. The “Freeway Revolt” led by the Glen Park “Gum Tree Girls” in 1958 catalyzed public opinion against unbridled development, at the same time that Jane Jacobs’ grassroots protest in New York had caught the public attention and led Robert Moses’ machine of Urban Renewal to a grinding halt. The Fontana Towers built in North Beach in 1960 were perhaps the last gasp of what was seen as the “Manhattanization” of San Francisco.

The lessons of distrusting developers and pro-development agencies were learned by the next generation, who were further galvanized by “Silent Spring” to suspect profit-driven development from an environmental perspective, and who embraced the National Environmental Protection Act (1969, Nixon) and the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA, 1970 Reagan) as tools for protecting their homes and neighborhoods from the impacts of rampant development.

Fast forward forty years, and the baby boomers who were champions of Civil Rights and environmental protections had become homeowners who are the face of Not-in-my-backyard protests against housing development, using NEPA and CEQA to block local developments of housing -whether affordable or market rate- for the noise, pollution, traffic congestion, and obstructed views that it might bring to their neighborhoods. The Sierra Club, far from promoting dense urbanism and transit-based low-carbon lifestyles, became one of the biggest opponents of affordable housing.

In the 2010s, the YIMBY (Yes-in-my-backyard) movement sprang out of activism by Sonja Trauss and the realization that the voices of tenants and potential tenants in San Francisco were structurally underrepresented in City Planning meetings because tenants were busy working to afford SF’s high rent. While YIMBY arguments went against entrenched neighborhood interests at the local level, they found fertile soil at the state level where the governor was perennially under pressure to solve California’s eternal housing crisis. Scott Wiener’s rise from a pro-development City Supervisor to a prolific author of pro-development state legislation brings us to the modern day, with bills like SB 423 and SB 79 marking the current battle lines.

For more background and context, read “Golden Gates” or watch “Fault Lines“

Factions and contentions

The voices on-stage and the questions from the audience helped me see three main factions in San Francisco housing politics:

- Tenants’ rights advocates, who oppose market-rate developments because market-rate development incentivizes landlords to displace long-term rent-controlled tenants

- Pro-development YIMBYs, who believe that easing housing production (particularly but not exclusively of market-rate units) is the best way to reduce prices across the market

- Preservationists, who oppose large market-rate developments because of the change that it will bring to close-knit communities and historic neighborhoods.

While we didn’t have anyone on-stage over the course of the week to represent the preservationist viewpoint, I corresponded with several leaders of preservationist organizations in preparation for the talk series, and have worked with them extensively in the context of my neighborhood volunteering.

The tenants’ rights and YIMBYs (Yes-In-My-Backyard) have found themselves sometimes on the same side of affordable housing projects, and sometimes on opposing sides of projects or ballot measures.

The preservationists and tenants’ rights organizations have a lot of overlap in shared emphasis on local control and developing processes which protect the rights of individuals, and have sometimes been allies in ballot measures and legislative proposals.

Over the last few years of engagement in SF housing, I’ve most astounded by how polarized these groups can be despite all sharing a small city, a shared set of facts about SF housing production, and a common Democratic Party umbrella. I’ve heard each group decry the other as a “loud minority,” even as each has received respective setbacks at the polls. I’ve been in communities which view Aaron Peskin as a saint and Scott Wiener as a corporate sellout, and in other communities where Wiener is viewed to walk on water and Peskin’s name is greeted with boos and jeers.

In reality, I think that the electorate is closely split between these two groups, and that both perspectives are important and have something to lend to crafting good policy. I think that the core challenge in finding common ground is that these groups have different values in structuring policy, and that each group has selective views of common facts.

This article will cover the different values that I see between the opponents of market-rate housing development (which I will refer to as “tenants’ advocates” but which includes a variety of viewpoints), and the pro-development YIMBY viewpoint. The next post examines some of the core facts and how they are viewed differently by the two groups.

Clashing Values: Narrative vs. Models

On stage during Manny’s Housing Week, I heard two very different ways of talking about San Francisco’s housing crisis: as a crisis composed of individual tragedies, or as a crisis of grand market forces. These two different perspectives lead to dramatically different approaches and strategies, and both can come off as callous to the other.

I heard compelling stories of families and grandparents facing displacement, and saw the importance that tenants’ rights organizations place in protecting those individuals. For advocates who are used to front-line direct action, a cautionary tale of a tenant displaced by a profit-driven developer is a scary portent of what all other developers might do. If the foremost priority is given to preventing the human tragedy of a family getting evicted, it can absolutely make sense to fight a developer from building hundreds of units on the site of a historic, rent-controlled building.

This perspective stands at odds with the YIMBY view, which might be best represented by the question “If we want low rents, why don’t we just build a f*ckton of housing?” – a question which drew cheers from the YIMBYs and outraged hisses from the tenants’ advocates. The core of the YIMBY argument is that San Francisco has added more jobs than housing, a problem which could be fixed by building more housing. For transplants and techies, this grand vision may be much clearer than the thousands of stories of individual tenants at risk of displacement as specific properties are considered for redevelopment.

Neither story is “right”, and it reminds me of the tragedy which played out in national politics over the last two decades: Yes, theoretical social well-being may be served by offshoring manufacturing in the 1990s and 2000s, but the political price we paid by creating millions of voters who wanted to Make America Great Again may not have been worth the short-term efficiency gains. Economics may fit well into mathematical models, but in politics both narratives and outcomes matter.

Clashing Values: Trust in Process vs. Trust in Prices

I think that everyone on stage would say that the housing market will always be inefficient- but there is incredible disagreement about who is best situated to manage that inefficiency.

The tenants’ advocates and preservationists want to see inefficiency handled through a robust appeals process, where the nuances of individual cases can be hashed out in front of an arbiter (often the Planning Commission or Board of Supervisors) and there is trust that the democratic process will ultimately work out in favor of justice- perhaps slowly, but always with the potential for rallying more support for the cases which really matter.

The YIMBY movement points to California’s extensive appeals process and opportunities for discretionary or CEQA review as being the source of the crisis, and -with the help of Senator Wiener and advocates like Ezra Klein– have been working to cut back on review.

Instead, this viewpoint trusts the price signals of the market as the best way of fixing inefficiencies. By building more market-rate housing, YIMBYs hope that high-earners will move into new units and out of older units, relieving pressure on the older building stock and reducing rent across the board – an approach which the tenants’ advocates would characterize as “only building luxury housing for the wealthy.” I vividly remember the flustered face from an audience member who interrupted Maria Zamudio to yell “but that’s just how efficient economic sorting works!”

Trusting economic sorting, marginal price signals, and competition can be theoretically clean, but the implementation -and the degree of protections from their lasting inefficiencies- leave the potential for the type of harsh narrative realities mentioned above.

Clashing Values: Government vs. Businesses

Similarly, the tenants’ advocates would like to see large-scale housing production put in the trust of the government, with an emphasis on social housing, a revitalization of government housing policies, and a normalization of public housing in the image of Vienna and Singapore. Because the government is answerable to the people and is bound to follow due process, they trust that at-risk or historically disenfranchised residents are best entrusted to the government.

The YIMBYs, meanwhile, want to see private developers breaking ground on large-scale housing projects, trusting that innovation can drive down prices as firms seek to reduce costs in order to maintain margins in a competitive market. Because developers have to compete and will work to find a way to utilize all opportunities, they trust that resources will be efficiently used and net social benefit will be maximized.

I think that part of this also may be a values difference between whether we need to design the system primarily to optimize outcomes for the most at-risk residents, or for the median resident. While efficient markets might be best at maximizing net social benefit (in this case by housing the most people at prices that they are able to pay), that doesn’t guarantee the best outcomes for those on the edge of displacement. In fact, a “both of the above” approach combining both new construction and strong protections for existing tenants has been found to be the best way of preventing long-term displacement.

Different Strategic positions: Where we stand

Standing on stage, I got a strong sense that each group would have a different view of what would happen if we were to freeze the current status of business, housing, and government right where they are now:

- The tenants’ advocates would be relieved: while the current situation is rife with injustices, it would give them a chance to prosecute current cases of injustice, unionize tenants, and address the needs of current residents without additional pressures from new proposed developments.

- The preservationists would be delighted: they want to preserve the city that they know and love, and would love the chance to enjoy the city without constantly fending off waves of tech booms and rich newcomers.

- The YIMBYs would be irate, viewing us as missing out on the opportunity to increase housing, produce more jobs, and create more opportunities for people and industries to move to the area.

This leads to both different tactics and outlooks when considering where we are and where we might go: while the YIMBY movement has a sense of urgency to drive change, the other groups can find it politically advantageous to slow-walk changes.

Conclusion

I’m honored to have shared the stage over the past week with so many people who are so passionate about SF’s housing crisis, and I learned an enormous amount in doing so. Despite the differences between the preservationists, tenants’ advocates, and YIMBYs, I honestly believe that they all deeply want the best for the city- but differ in the techniques and tools which will get us to that brighter future

Next up, I’ll be examining some of the key facts which undergird this discussion, and lead to dramatically different views despite living in the same small city.

Leave a comment