During SF Housing Week at Manny’s, and throughout the SF Housing Element, a common refrain I heard was that “SF has a lot of vacant units- why do we need to build more units when we already have a lot of extra capacity?”

I want to dig into this and the uniquely SF reasons for keeping units vacant which I’ve seen from my travels through the housing world, specifically:

- High-end units being informally merged

- Units being held off-market because of rent control’s impact on multi-family prices

- This speculative activity being exacerbated by Prop 13

- Investment-only properties in the mix

Some Data, and some trends

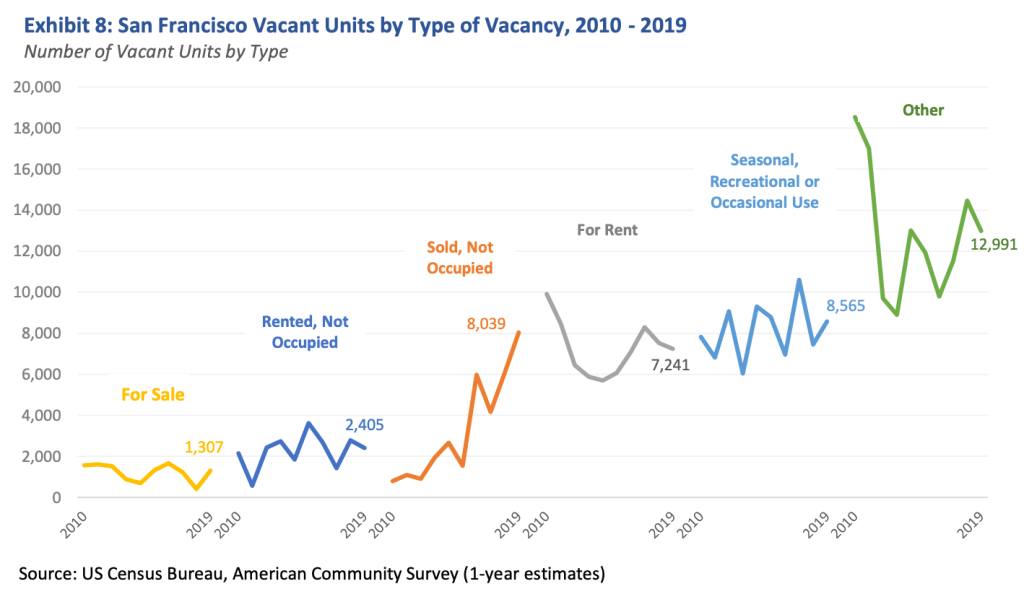

A 2022 report from the Bureau of the Legislative Analyst prepared ahead of Prop M outlines the trends in unoccupied units across major categories, based on the American Communities Survey- most are relatively stable as a portion of the housing stock, with two notable exceptions: “Other” category, and “Sold, Not Occupied”

The “Other” category includes foreclosures, which is why the 2010-2011 numbers are in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, but then return to lower steady-state levels. Because this category and the “seasonal, recreational, or occasional use” categories include all manner of other excuses for keeping a unit vacant, they are the areas where I suspect the interesting stories are to be found.

The “sold, not occupied” category is probably the reflection of real estate as a place to park investment funds: In 2014-2015, there was a surge of overseas buyers buying SF real estate: this is probably their impact showing up in the ACS numbers. This is similar to other high-cost cities (Vancouver, New York) where foreign investors have put cash into the market to launder funds, speculate on future returns, or diversify away from paper assets.

Comparison with other cities

Using the same American Communities Surveys, the report flags that while SF has slightly lower than median market vacancy rates, it has slightly higher than median total vacancy rates- indicating a tight market, but one where units are also being held off the market. The report was written using American Community Survey data from 2019; revisiting that shows that SF’s total vacancy went up slightly during the intervening years (likely associated with SF’s pandemic impacts) but the conclusions from 2019 generally still hold.

This means that overall, if SF were to revert to normal vacancy rates, another ~12,000 units might be added to the market- of which about 5,000 are from investment properties, and about 7000 are from the “occasional use” category of off-market vacancies vacancies surveyed in the ACS (the “other” category of ACS vacancies is comparable between SF and other cities). Let’s dig into some surprising reasons why that might be the case…

Informally merging units to create luxury

For those who want to live in luxury with 4+ bedrooms, the cheapest way to create a luxury experience is likely to be buying a multi-family building, and (informally) merging the units. While formally removing units from the housing market is near-impossible, it’s informally done commonly and brazenly.

A great example of this is 3800sqft triplex at 824 Vallejo Street: built as a triplex and last sold as a multi-family house in 2007, it was recently put on-market “arranged as a single-family home” with 5 bedrooms & 6 baths. Listed at $3.4M in 2025, it is actually a relatively cheap way to buy into luxury: Because single-family homes in San Francisco sell at such a premium per square foot to multi-family buildings, it would be much more expensive to buy buy a luxury condo or a single-family home with the same floorspace and finish.

You don’t need to go far to see examples of this: Aaron Peskin lives in a two-unit building of which he keeps one unit vacant, using it as a guest room or space for entertaining. During his 2024 mayoral race, I was at a town hall when Peskin flat-out turned down the chance to rent his vacant unit when a constituent asked directly “I’m a recent transplant with good credit and employment, who’s having a hard time getting my own place in SF. If occupying vacant units is so important to you, would you rent your extra unit to me?”

Peskin may not have originally intended to keep his unit vacant an off-market (he and his wife inherited the property), but may have expanded into it when the unit was vacant and they found their needs for space growing. In a healthy housing market, they may have found it more effective to move to a unit that fully met their needs, rather than being locked into a property which they had inherited and for which they paid a relatively low tax rate (Peskin’s annual tax bill for the property in 2025 is about $13k/yr).

Prop 13 and low carrying costs

If it’s inconceivable that a landlord might forego tens of thousands of dollars a year in rent, there’s a piece that you’re missing: tax limits from California Prop 13.

California’s Prop 13 caps property taxes at 1% of assessed value, and caps the increase in assessed value to 2%/years except when it is sold, resulting in a very low tax burden for buildings which have been held for a very long time: When I bought my property in 2022, the previous owner had held it for nearly 60 years, and the assessed value went from $90k to $1.64M (from 2.4k in taxes to $24k/yr in taxes).

As a result, long-term property owners have extremely low carrying costs for housing- an asset with good expectations of upside, but volatile changes in housing prices. When it’s cheap to make a bet on future housing appreciation, it may make sense to just keep holding the unit vacant, then sell when the market spikes up.

The impact of rent control

Multifamily properties are typically calculated based on “cap rate”, simple formula which lets you estimate a fair price based on the rent and expenses of the building. For a 5% cap rate (a good assumption), a $1 increase in rent means that property value goes up by $20.

In San Francisco, long-term real estate property appreciation is about 6%/yr (averaged since the 1960s), which means that mortgage payments for those considering getting into the market also go up an average of 6%/year. If people will rent as long as it’s cheaper than buying, long-term market rate rent growth would also be 6%/year.

This means that long-term, the owner of a multi-family property could also expect their building to appreciate at about 6%/year if rents stay at market rate.

However, rents in San Francisco are controlled to not raise at more than 2/3 of the consumer price index (CPI) increase, or a target long-term average of 1.3%/year.

This means that if a property owner were to keep their multifamily property fully vacant, they would get a 6%/year return, but if their property is fully rented it will only appreciate at 1.3%/year. Because SF has no vacancy control, there’s a strong incentive to sell the property at a time when the most units are vacant or recently rented, and its value is based on market rents. To do this, owners can evict tenants (unscrupulous, mostly limited by eviction protections, Ellis Act, and owner move-in eviction rent limitations), hold the unit vacant, or sell when a tenant moves out.

Policies to address this

The profit between holding a unit vacant and renting it out to rent-controlled tenants needs to be closed. The successful 2022 San Francisco Prop M ballot measure authorized a tax on vacant units, but it’s tied up in courts, had significant loopholes, and penalties are light enough relative to the scale of property appreciations that they may not close the gap.

The big per-square-foot gap between single-family homes and multi-family homes in San Francisco will continue to tempt people to informally merge units until there is an easier alternative for moving into larger units. Right now, zoning and discretionary review processes limits the supply of luxury inventory, and the condo conversion ban keeps units from moving from the rental market to the ownership market to legally fill the supply, keeping up a price difference which people will exploit by merging units informally.

Perhaps our guiding light should be a world where Aaron Peskin would find it easier to buy a new house than to live in both halves of his duplex.

A countervailing, skeptical viewpoint: The Frisc coverage of Prop M

Leave a comment